World Obesity Day: 5 things to know about weight stigma

11 October 2018

James Nobles (@JNHealth) is a Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol working in the NIHR CLAHRC West team. Stuart Flint (@DrStuartFlint) is a Senior Research Fellow in Public Health and Obesity at Leeds Beckett University, where he is part of the management team of the Applied Obesity Research Centre. In this blog post, first published on the Food Active site, they discuss weight stigma, and answer some commonly asked questions.

The theme of this year’s World Obesity Day is weight stigma. But what is it? Who does it affect? Why is it harmful to individuals, to society, and counterproductive to system wide efforts to create a healthier environment? Over the last few years, we – amongst a host of others – have been working to increase awareness and understanding of weight stigma, and perhaps more importantly, to influence how society, the media, and the Government think about obesity. Within this blog post, Stuart and I answer five common questions about weight stigma.

- What is weight stigma?

Weight stigma is a social devaluation of people with overweight and obesity. Their weight, shape and size doesn’t comply with the dominant and enforced social norms. It can be viewed on a continuum: weight stigma (for example, assuming people with obesity lack willpower) leads to bias (treating people with obesity differently to others), which in turn creates discrimination (such as removing access to healthcare based upon a person’s weight).

- Who does it affect?

Weight stigma, bias and discrimination has profound and harmful impacts on people across the weight spectrum, particularly on people with overweight and obesity. Women are also more likely to experience weight stigma, compared to men. People with overweight and obesity who experience weight stigma and discrimination are more likely to have poorer mental health, poorer eating behaviours, avoid exercise and healthcare settings. This can in turn lead to gaining more weight.

Weight stigma is pervasive; it lurks where we would least expect it. Children report weight stigma in educational settings from teachers and peers. Patients with obesity often experience lower quality treatment from clinicians, nurses, and dieticians. Weight stigma is evident in public health messaging and campaigns (e.g. Cancer Research UK’s ‘OB_S_ _Y’ campaign), with such campaigns suggesting that obesity is a modifiable lifestyle behaviour. Across society, weight stigma can be seen in workplaces (from colleagues and management), the media, and social situations.

- Why is weight stigma so pervasive?

The media is a primary contributor to weight stigma. Every day, sensationalist headlines about obesity are broadcast to the public, alongside simplistic explanations of the causes of obesity and its ‘cures’. Media portrayal is often inaccurate, stigmatising and derogatory. For instance, this week we saw the headline below published in The Sun. These newspapers, collectively, are read by millions of people. When combined with online media, such inaccurate portrayals subtly influence public attitudes about obesity.

“Obese kids ‘should be put in CARE and their parents

sent to boot camp’, says TV diet guru”

The common simplification of obesity – caused by overconsumption and insufficient activity – fuels the fire. Most people have strong opinions about obesity, particularly about the causes and solutions, and many can recall examples of family or friends who have “successfully” lost weight. The dominant public perception is that obesity can simply and rapidly be cured by “eating less and moving more”. As people seek evidence to confirm these beliefs, the media stoke the fire by cherry picking ‘evidence’ to support public perceptions, irrespective of the science and literature telling us otherwise.

- Why is it important to understand weight stigma?

Weight stigma, bias and discrimination – among other reasons – prevent an effective population and system wide approach being taken to create healthier environments. There are real improvements to be had from eradicating weight stigma. People with obesity would be more likely to access effective and patient-centred care, care which is delivered by compassionate and knowledgeable practitioners. Governments would be more likely to tackle the structural drivers of weight gain if seeing obesity as a product of the wider determinants of health, such as employment, education, access to healthcare, housing quality and so on, rather than that of poor individual lifestyle behaviours. Weight stigma is a significant hurdle to overcome.

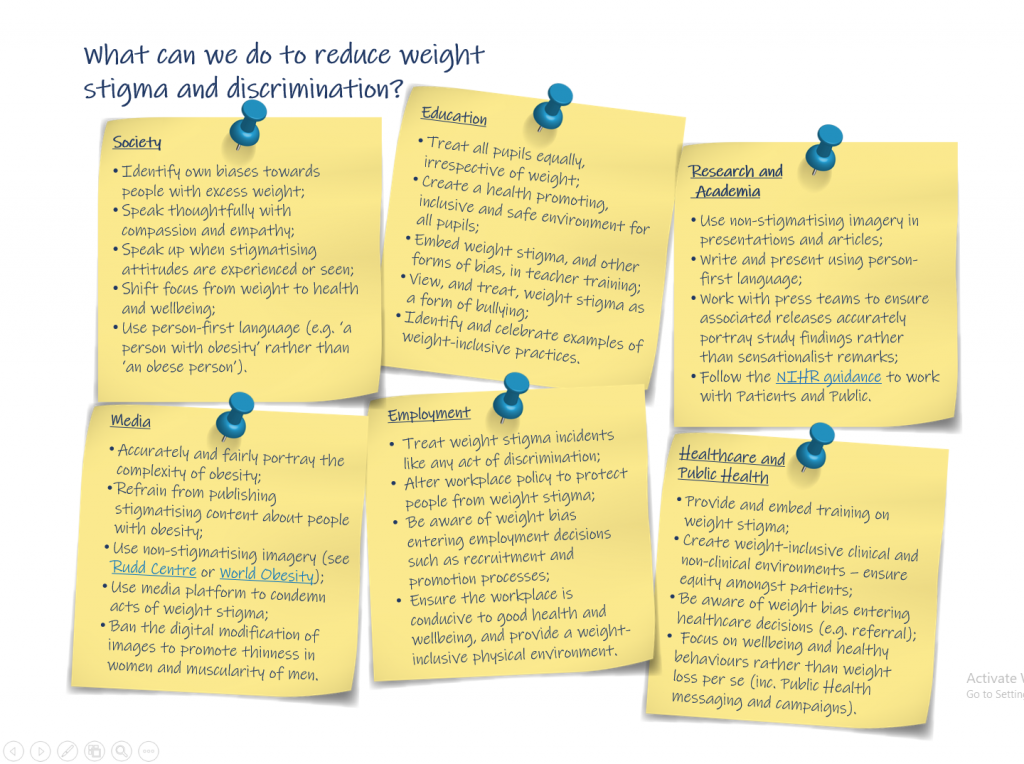

- What can we do to reduce and eliminate weight stigma?

People with obesity are said to be the last acceptable targets of discrimination. Weight stigma is so ingrained in our society that action is needed at every level. Government and policy makers must lead from the front, avoiding stigma, problematic framing of obesity and reduce blame in policies, campaigns and other public facing messages. As individuals, we should reflect on our own attitudes, beliefs and behaviours that may be stigmatising and discriminatory. It’s likely that many of us have stigmatising attitudes towards overweight and obesity given the consistently stigmatising messages we receive. This doesn’t make it right. We must all change and we all have a part to play in reducing weight stigma and discrimination.