Why we need alternative types of evidence to inform policy around the prevention of childhood obesity

10 February 2021

Dr James Nobles, Senior Research Associate at NIHR ARC West, blogs about a newly published secondary analysis of the studies underpinning the Cochrane Review on preventing childhood obesity.

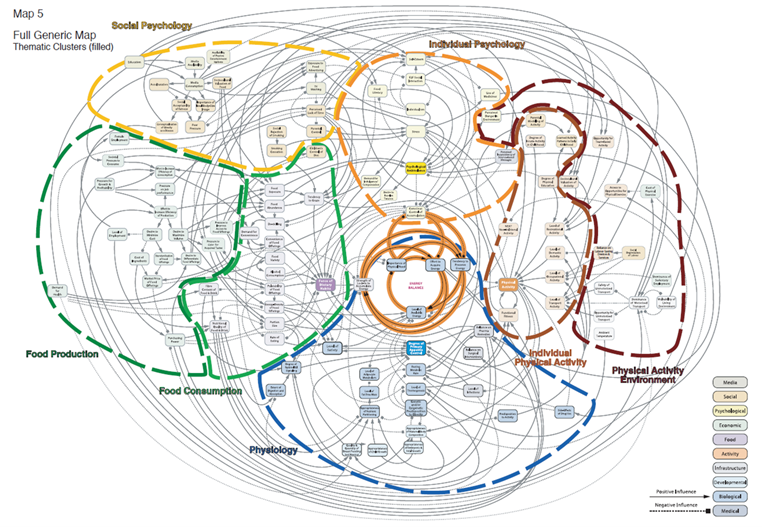

Many of you will have seen the Foresight map before which resembles a plate of spaghetti (Figure 1). It illustrates the complex causes of population-level obesity, and that the majority of these causes are beyond an individual’s control. The last decade has seen a compelling case emerging about the need for systems approaches to help prevent obesity. A systems approach would mean that multiple organisations and sectors work together to try and change our obesogenic environment (so persuasively shown in the Foresight map) to one that is more conducive of better health outcomes.

Figure 1: The Foresight obesity map

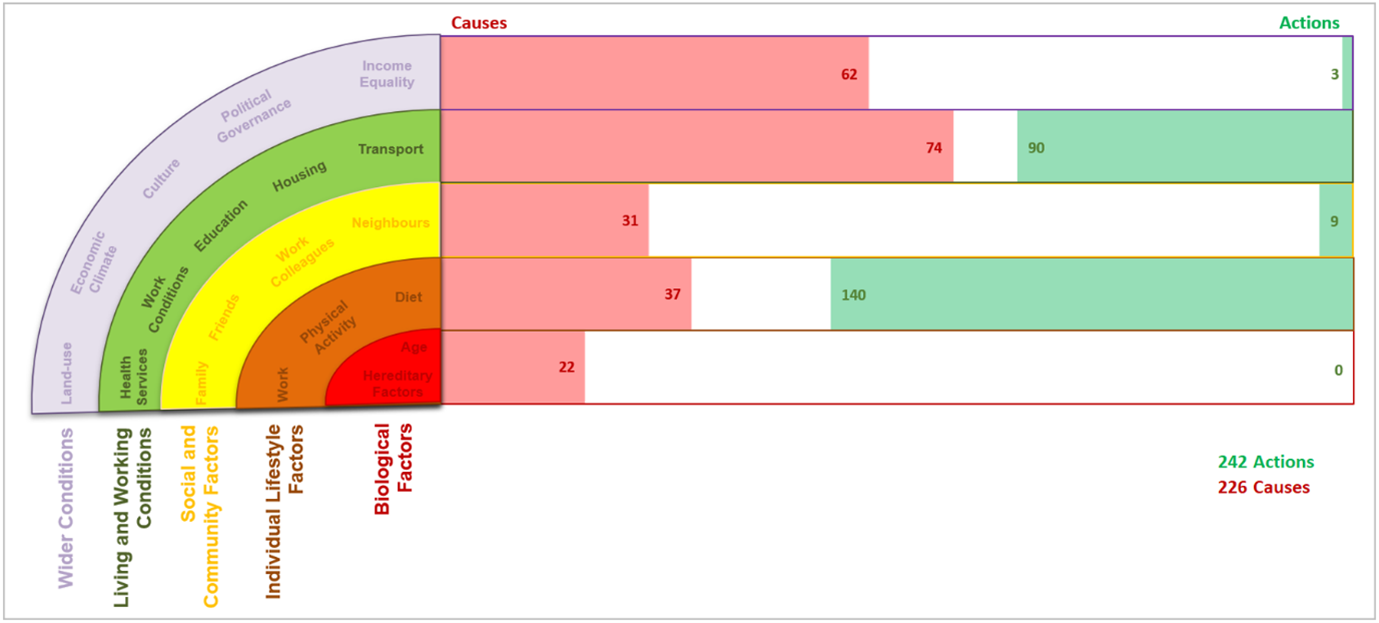

In a previous research project, we wanted to get a better understanding for how local authorities were working to prevent and treat obesity. What we found was stark. Across the 10 authorities that we worked with, 228 actions were being implemented to prevent or treat obesity. Almost two thirds of these actions aimed to change individual lifestyle behaviours (such as the amount of physical activity people do or what they eat). Very little intervention was concerned with changing the environments that people live in.

This got us questioning why. Why do we try educating people to make healthier decisions rather than changing the environments that we live in? We speculated that one reason might be the evidence base, the reverence for the randomised controlled trial, and in turn, evidence-informed policymaking.

Randomised controlled trials are often viewed as the gold standard research design for providing empirical evidence. These trails are then synthesised in rigorous reviews to provide recommendations for policymaking, practice and future research. Cochrane – the global research collaboration – publishes arguably the most robust and rigorous evidence syntheses. As such, they are highly regarded by governments across the world.

There have been four Cochrane reviews published around the prevention of obesity in children: the first in 2002 (included 10 studies), the second in 2005 (22 studies), the third in 2011 (55 studies), and the most recent in 2019 (153 studies). Each review includes all the studies of its predecessor, plus any new studies that have been undertaken since. It’s safe to say there is a lot of evidence to synthesise in these reviews!

Our recently published project evaluated the focus of the 153 studies included in the 2019 Cochrane review. The results showed that almost 60 per cent of intervention effort was placed on educating people, predominantly children, how to make healthier decisions (Figure 2). We found that quite a lot of focus was also placed on changing the school environment, but when we looked more closely at this, much of it was about teacher / staff training. This training would then equip school staff with the knowledge and skills to teach children how to make healthier choices.

We also compared the focus of the studies between 1993 (the oldest study in the Cochrane Review) through to 2015, but didn’t find any differences; the focus remained steadfast on changing individual behaviours.

Figure 2: The focus of obesity prevention studies included in the Cochrane review

So this went someway to answering our previous question; could the evidence base influence the type of policies and interventions being commissioned? We think that the short answer is yes, perhaps. If policymakers are required to draw on evidence to inform their decisions, and if a preference is placed on high-quality randomised controlled trials, then this would lead them to focus policies on interventions targeting individual lifestyle behaviours.

Where does this then leave us? Well, we think that there are some key implications for policy- and decision-makers, for research councils, and for researchers.

- Policymakers should be attuned to this bias in studies that predominantly seem to address individual behaviour change.

- Research councils could fund alternative study designs (such as natural experiments) that may be more suited to complex issues like the prevention of overweight and obesity.

- Researchers should try to evaluate changes and adaptations to a system rather than trying to determine if a single intervention affects something as complex as the prevalence of obesity. It is highly unlikely that this will be the case.

- Researchers and policymakers could work more closely to ensure that new policies are effectively evaluated, and subsequently, that the evidence from these studies goes on to inform future decision-making.

Many public health issues, including obesity, are complex. We can’t expect single interventions and policies to shift the dial on this alone, to do it in isolation, and to do it within a short timeframe. Research and evidence should contribute to innovative and complementary solutions as we move forwards, but the role of the randomised control trial is a little less clear in circumstances like these.

Paper