Low versus high dead space syringes: user preferences and attitudes

People who inject drugs support the use of new, safer ‘low dead space’ syringes, our research has found.

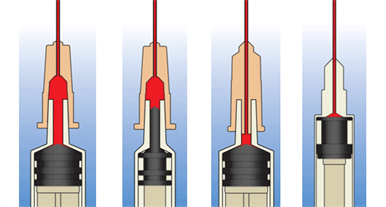

A low dead space syringe has less space between the needle and the plunger when it’s fully pushed in, compared to traditional injecting equipment. It also has a detachable needle. The ‘dead’ space in a syringe holds blood after it’s been used. Previous research has found that low dead space syringes could reduce the chance of spreading infections, such as HIV and hepatitis C, if they’re re-used or shared.

This diagram shows how syringe design can affect the amount of blood collected and transmitted when sharing needles. The far left shows a very high dead space syringe, and the far right is the lowest.

Needle exchanges supply sterile equipment to people who inject drugs, to stop people having to share with others. But sometimes equipment still gets re-used or shared. If exchanges switch to this new type of syringe, it would help protect people from infection.

But we didn’t know if people who inject drugs would be willing to use this new equipment.

This project was a collaboration with the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit (HPRU) in Evaluation of Interventions.

Project aims

We aimed to find out whether people who inject drugs would be willing to switch to this new, safer equipment.

What we did

We reviewed the existing research on these syringes and whether people minded using them. We also interviewed 23 people who inject drugs, and 13 volunteers and professionals who work with them, from Bristol and Bath. We aimed to explore their views on detachable low dead space syringes, and decide whether any additional support is needed to encourage their use.

How we involved people

The Bristol Drugs Project (BDP) provides needle exchange services in Bristol. People who use BDP’s services were on the project steering group. Involving people who inject drugs was vital. They offered important insights into our findings and plans for implementation.

It can be a challenge to engage with people who inject drugs because of their addictions and circumstances. BDP identified which of their service would be willing and able to participate in the steering group, and helped them attend meetings.

From the BDP service user perspective, this project was an enjoyable and empowering experience. We learnt how valuable it is to enable their engagement, through practical support and by making an effort to explain the terms used during meetings.

What we found and what this means

Decisions about injecting, including the choice of equipment, where to inject on the body and whether to rinse or re-use equipment, were influenced by a number of things. These included early experiences and being shown how to inject by others, and availability and awareness of alternative equipment. Avoiding or minimising problems such as difficulties finding a vein, vein damage and collapse, or pain due to abscesses and infections was also a factor.

The relationship between rinsing and re-using syringes was complex: not rinsing risked re-use of unclean syringes if there was a shortage, while rinsing could encourage re-use.

Most people who inject drugs found it difficult to change injecting equipment. If there weren’t any problems they saw no need to change and preferred using their usual equipment. However, if they did experience problems they tried to address them, and if there was a perceived benefit they may be willing to consider change.

An important barrier to change was prioritising getting a hit quickly over preventing future problems. As one participant said:

“I don’t want to get infections … Because I can be quite lax on thinking this stuff at the time, so I think that is quite important. Yeah definitely, lower the risk of transferring infections. (…) You get the thinking of I will deal with it later, if I get an illness I will deal with it later.”

Needles and syringes were not only a tool for injecting the drug, but they also formed part of a familiar routine. We thought it was likely people would be frustrated by having to change from familiar equipment, but that most people would be willing to try the new syringes if they understood the benefits. We thought they’d continue using them if they worked as well as the original equipment.

Our research found support among people who inject drugs for the new equipment. They valued the benefits of less wasted drug, as there is less left in the syringe after injecting. They also valued the lower risk of transferring infections. Another participant commented:

“Less waste is obvious isn’t it, no-one wants to waste anything in life, but drugs, since it is our obsession, it’s the most important thing.”

A needle exchange staff member said:

“It’s a really helpful intervention (…) I don’t have to talk about diseases and viruses and stuff, but these syringes here, you get absolutely all your drug.”

For needle exchanges, we have developed recommendations for introducing detachable low dead space syringes, based on our findings from the review and interviews. These include:

- training needle and syringe programme staff

- education for people who inject drugs

- offering a few low dead space syringes to try with usual equipment, and eventual restriction of the usual equipment

Alongside the introduction of the new syringes, encouraging appropriate rinsing methods among those known to re-use or share equipment may also be necessary.

What next?

This research has helped Bristol Drugs Project to anticipate and respond to people’s worries about low dead space syringes. Some people using their service are now beginning to accept them.

We have developed materials to support introducing these syringes, including a flyer for needle exchanges to inform people who inject drugs about the new equipment. We are also developing a step-by-step guide for needle exchanges.

Our findings are relevant to the National Institute of Clinical Excellence and Care (NICE) who produce guidance for needle exchanges.

Rachel Ayres, Volunteer Manager, and Jane Neale, Needle Exchange Manager for Bristol Drugs Project, said:

“The materials developed by the research team will help us to continue to increase the number of people who switch to low dead space syringes. We believe they will also be useful to support other needle and syringe programmes to introduce low dead space syringes effectively too.”

Paper

Acceptability of low dead space syringes and implications for their introduction: A qualitative study in the West of England

Read the paperRelated research project

This research was implemented through a project to develop materials promoting the use of low dead space equipment among people who inject drugs and needle and syringe programmes.

Links and downloads

- This video presentation explores the findings from this research in more detail Watch the video presentation

- Rejoinder to: Implementation of low dead space syringes in response to an outbreak of HIV among people who inject drugs: A response to Kesten et al.s Read the rejoinder (subscription required)

- Drug and Alcohol Findings have published a research analysis of this study Read the research analysis

- Exchange Supplies have published a low dead space briefing which includes our findings Read the briefing

Lead collaborators

- Matt Hickman, University of Bristol

Partners on this project

Bristol City Council

The council plays a vital role in the health community as public health is part of its remit. Its role is to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among the population of Bristol. Its activities aim to provide conditions in which people can be healthy and it focuses on the population as a whole, not on individual patients or diseases.

University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is internationally renowned and one of the very best in the UK, due to its outstanding teaching and research, its superb facilities and highly talented students and staff. Its students thrive in a rich academic environment which is informed by world-leading research. It hosts the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research.